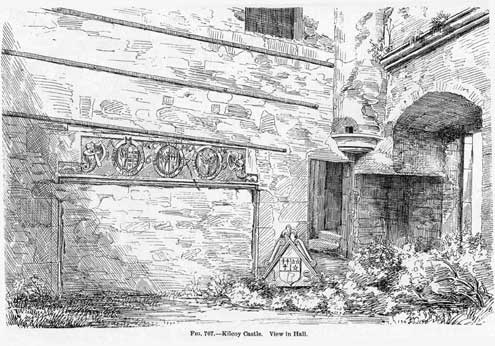

Detail of drawing from ‘The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland’ by MacGibbon and Ross (1887) p 253 (see below for more information).

Trying to place a firm date on the demise of the harp in Gaelic Scotland is probably a self–defeating exercise as the evidence tends to suggest a slow fading away as the musicians themselves died rather than a total and abrupt collapse. What is becoming clear however is the contrast between Scotland and Ireland where the direct link between harper and File or poet had more or less ended by the start of the 17th century with evidence showing that the Irish harpers were starting to experiment with chromatic stringing and seeking employment that was not linked to supporting the declamation of syllabic verse. For Ireland most of the 17th century was a fairly traumatic period and when the post Cromwellian recovery came, it coincided with the appearance of the larger high headed harps which although still diatonically tuned, in the hands of Carolan and his contemporaries, the music they played was largely influenced by the popular Italian composers and were, with a few exceptions, playing mostly music catering to popular musical tastes. Within Gaelic Scotland change seems to have been less abrupt with the status of the harp and harper along with that of the poets, simply undergoing a slow decline over the course of the 17th century.

The Mermaid Harpers from the fireplace mantle at the ruin of Kilcoy Castle in Ross–shire carved in 1679 a little before the use of the clarsach went into decline. The drawing is from ‘The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland’ by David MacGibbon and Thomas Ross, volume II, 1887, page 253.

[You may click on the picture to view a larger–sized image]

So far there is no evidence in Scotland that parallels the Irish attempts to make chromatic instruments, although that may be partly due to the fact that the gut strung Lowland harps were still flourishing and would have catered for the audience that the Irish harpers were trying to reach. Nor is there any sign within the Scottish Gaidhealtachd of the ‘Carolan’ effect which was probably a considerable factor in extending the harp’s use in Ireland until the end of the 18th century. Turning to the Scottish evidence, although at least two harpers, one professional and one amateur were still active towards the middle of the 18th century, the critical period for the clarsach’s decline seems to have been the two decades either side of 1700. Certainly as that period was approaching a harp was still regarded as a valuable possession judging by an assignation dated 1672 concerning a harp then in the possession of Lady Ardnamurchan but which belonged to George Campbell of Airds and his son John, who were passing their rights to the instrument onto Lord Neill Campbell.[1] Likewise some of the harpers around at that point were highly enough thought of to be able to make a comfortable living judging by some of those about whom we have a reasonable amount of information.

Duncan McIndeor harper to Campbell of Auchinbreck, who died in 1694 was the prime example and although his home was at Fincharn at the South West end of Loch Awe, he seems to have been equally at home in Edinburgh where he can be identified as the ‘Duncan Dowrie blind herper’ whose unnamed young child was interred in the Greyfriars Kirkyard on the 16 March 1694, which also explains the gap left in the list of his children’s names in his own testament dated later that same year.[2] Another contemporary blind harper also demonstrates a fairly wide geographical ‘circuit’. A receipt, endorsed on the outside as ‘for Pat dalls meall’ is actually signed for on the harper’s behalf by a John Allan living in Campbeltown having received from ‘Andrew Grant, servitor to Lord Neill Campbell, two bolls of meall & that in Patrick McErnace harpers account’, dated 1683. Although why the receipt should have actually survived among the Breadalbane papers is somewhat of a mystery.[3]

In 1698, just as the seventeenth century is drawing to a close, another harper appears with connections to the Robertsons of Lude. His name was Manus McShire and he is noted in an account book containing material connected with the Barony of Lude, covering the period 1688 to 1704, which is mixed up with the Logierait Kirk Session records. There is no obvious connection with the Kirk Session and the entries are mostly household and similar payments, including apart from the harper, payments to violers as well as the purchase of a base and treble viola.[4]

If this additional evidence of harpers is added to the number already identified as being around at the turn of the century, (including those whose lives spanned both sides of 1700), then there were at least ten professional and three amateur harpers flourishing at that time. However, apart from a harper called ‘Neill Baine’ who according to a letter dated July 1702, from Farquhar MacCulloch, a servitor to Allan MacDonald of Clanranald and addressed to MacKenzie of Delvin, had been made so drunk by the servitor that he was not able to tune his harp, but was presumably otherwise healthy and another called Angus MacDonald who was given £6– 9sh upon the instructions of Menzies of Culdares on the 19 June 1713 plus the intriguing record of a payment to ‘two harpers by my Lords order’ under the year 1714 in the Marquis of Huntly’s accounts, it is noticeable that there have been few new harpers added after the end of the seventeenth century.[5]

In fact of those harpers we know, the term ‘a dying breed’ would prove most apt as from Alexander Menzies, (died 1705), Robert Robertson, sometime in Stralloch, (Testament 1713), Rory Dall Morison, (died circa 1714), through to Lachlan Dall, (died circa 1721–27) and Murdoch MacDonald, (circa 1740),[6] the list becomes one of obituaries rather than a flourishing tradition. Even if we turn to the three known amateur players it is a similar pattern with John Robertson of Lude, (died 1730), Ranald MacDonald of Cross , (died circa 1730–40)[7] and Alexander Grant of Shewlgy, (died 1746).[8]

Picture of the 1679 fireplace lintel following the restoration of Kilcoy Castle and conversion into a private home.

(Photo © by Keith Sanger)

So returning to the last few decades of the 17th century and the question of whether the tradition at that point was flourishing or simply part of a long slow decay?

Well, comparison with what happened in Ireland suggests that the answer is both, depending upon how the evidence is assessed. Both the harpers and pipers, along with the poets were at the top end of the ‘sponsorship’ tree. At that period the support upon which they all depended came from the echelons of a predominantly Gaelic society, the equivalent of today’s Arts Council support, analysis of which shows that most of the money ends up supporting just a few organisations, Scottish opera, orchestras and theatres, the modern equivalent to the old musician supported poetic orders. How many there are of these is in turn dependent on population size, and if we return to 1700, the population of Scotland is estimated to have been around one million, with about half of those being Gaelic speaking, roughly equivalent to the population of Edinburgh today. Placed in that context the identification of at least ten professional harpers does seem proportionate and healthy. In Ireland over that same period the population was recovering from the Cromwellian excesses and by 1700 had probably reached around two million people. Between then and 1790 it more than doubled to some five million people and as the greater part of that increase came from the poorest section of the population, mostly Catholic and Irish speaking, it meant a considerable increase in Gaelic speakers to the extent that there were probably, in absolute numbers, more Gaelic speakers than ever before. It was into the beginning of this surging population that O’Carolan and his contemporaries were born, but despite this much larger population base along with the adoption of the more popular contemporary Italian musical styles, only ten Irish harpers appeared at the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792 and had mostly all gone within the next twenty years.[9]

Even allowing for a few more harpers who did not make it to Belfast, the number of harpers relative to the total Irish population suggests that they were in a much weaker state than the comparable position in Scotland circa 1700. However there are several factors that have coloured subsequent history. Firstly, by the late 18th century interest in ‘preserving’ the past had become fashionable, for example, the Highland Society Competitions for Piping which commenced in 1781, and which may have provided the inspiration for the Belfast Harp Competition, (Dr James MacDonnell, one of the principle instigators of that event, had been a medical student in Edinburgh at the time of the early piping competitions).

Secondly along with the attempts to record the harpers’ music came some antiquarian efforts to preserve the harpers’ instruments, which given that there were still more than ten practising harpers meant that there were some instruments around to preserve and probably explains why all the surviving later wire–strung harps have an Irish provenance. But returning to Scotland circa 1700 and what I have suggested may have been a relatively healthier state by comparison, not only were there no antiquarian movements attempting to preserve the music and instruments, but there is possibly a third factor which may have led to the steady decline of the harping tradition as the harpers themselves died. Unlike Ireland, there is no evidence to suggest that the players of the clarsach or wire–strung harp in Scotland made any concessions to the Italianate styles of music that were becoming increasingly influential around that period, but that their music was rooted firmly within their native Gaelic environment. In turn as their patrons began to straddle both the Gaelic and Lowland Scots world, and as the cultural influence of the latter grew the clarsair gave way to the more chromatically versatile ‘violer’ whose appearances in the various estate accounts from 1700 onwards occur in ever increasing numbers.

By the middle of the 18th century violers, or in some cases described colloquially as ‘fiddlers’, were present even in the main MacDonald heartlands, for example, a Gilbert Macphauk in Skye,[10], Donald McIllocoirue in Keppock,[11] John Mclsaak at Kinlochmoidart and Peter Grant in Glenurquhart.[12]

[1] National Archives of Scotland, (NAS), Acc 20012/7 Box 3, Bundle 44; For the family and their interconnections see, Alastair Campbell of Airds, Unicorn Pursuivant, The Life and Troubled Times of Sir Donald Campbell of Ardnamurchan, The Society of West Highland & Island Historical Research, (1991).

[2] NAS, CC2/5/2/57, (cf Sanger K, Auchinbreck’s Harper, West Highland Notes & Queries, Number XXX, February 1987); O.P. R. Deaths 685/010087 Edinburgh

[3] NAS, GD 112/2/113/3/39

[4] NAS, CH2/694/10

[5] Stewart, James A. The Clan Ranald: History of a Highland Kindred, (Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 1982, available via the British Library EThOS, electronic theses online service), 314, quoting NLS MS 1105/143; NAS, GD 50/148/17/16 and GD 44/51/167/5.

[6] A Coll tradition claims that ‘Eoin MacMhurichidh Chlarsair’, the harper’s son John could play the harp having had some tuition from his father before they argued over his lessons and the son lost interest. For a discussion of the source and authenticity of the tradition see Sanger K, MacLean Harpers, some loose ends. West Highland Notes & Queries, Series 3, Number 15 (October 2010).

[7] While there are numerous traditional tales associated with Ranald hard information is lacking. Even his usually accepted dates given in the various Clan Donald histories of circa 1662–1741 are not backed by references. One firm date occurs in a 1705 ‘List of Papists in the Shire of Inverness’, (National Archives of Scotland CH1/2/5/3f.177) where strangely he is listed not in Egg but in Morar after Allan MacDonald vic Coul of Morar, as Ranald M’Donald of Cross his brother. A circumstantial case can be made that he in fact had died before 1715 and probably can be linked to a reference dated 1712.

[8] For full details of these harpers see Sanger, K & Kinnaird, A. Tree of Strings, (1992), Appendix F.

[9] Yeats, Grainne, Feile na gCruitiri Beal Feirste 1792, Gael–Linn, (1980).

[10] NAS, CS96/426l/62, Factors Account Book, Sir Alexander MacDonald of that ilk covering 1732 to 1746. The fiddler first appears in 1745 receiving an allowance of £11 which compares with the pipers. Charles MacArthur at £49–6sh–8d, his father Angus ‘the old piper’ receiving £19–2sh, John MacArthur in North Uist at £33–6sh–8d and ‘Ewine Mc Intyre’ in Slate at £17–1sh–4d. In reality the pipers were sitting rent free and these sums appear in the discharge side of the accounts to balance the total potential rental the estate should have otherwise provided. Similar payments are listed for among others, the cost of maintaining a boats crew.

[11] NAS, GD44/11/2, listed at ‘Leanachanbeg’ in 1755

[12] Livingstone of Bachuil. A, Aikman, W. H, and Hart, B. S. eds. Muster Roll of Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s Army, 1745–46, (1984). 143 and 153.

* An earlier version first appeared under the title “Final Chords” in West Highland Notes & Queries, Series 3, No 14, the Bi–annual publication of The Society of West Highland and Island Historical Research. Breacachadh Castle, Isle of Coll, Argyll, PA786TB. Scotland.

Submitted by Keith Sanger, 2 July, 2012

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.