When he died in September 1694 Duncan McIndeor appears to have been one of the wealthiest harpers of his generation. His testament was one of the most extensive among the few which survive for Scottish harpers. [see testament below] He lived at Upper Fincharne

, now just described as Fincharn, which lies on the south side of, and two miles from, the southern end of Loch Awe in the Parish of Glassary.[2] Fincharn and the nearby ruined church and grave yard of Kilneuair, (where Duncan was probably buried) were both part of the lands of the Campbell’s of Auchinbreck and in the testament Duncan McIndeor is described specifically as harper to Sir Duncan Campbell of Auchinbrek

.

Fincharn Farm; see footnote [2] for details

Photograph copyright 2016, WireStrungharp.com

According to the testament he was survived by his wife Christine and three daughters, Mary, Katherine and Jean, while there was a space left for another name. The reason for the name having been left blank can be explained by the fact that apart from his main home at Fincharn he also had a home in Edinburgh and according to the Edinburgh Greyfriars Kirk Records an un–named child of Duncan Dowrie blind herper

was buried there on the 16 March 1694. This entry also shows one of the stages in the transformation of the original Gaelic name of Macindeoir meaning son of the deoir

to its modern form of just Dewar.[3]

That Duncan McIndeor, who we also know from that burial record was blind, served the Auchinbreck family may explain both the Edinburgh home and provide some explanation for his wealth. Sir Duncan Campbell of Auchinbreck (d. 1700), was the nephew of Sir Dugald Campbell of Auchinbreck who had died unmarried shortly after the restoration of King Charles in 1660. Sir Duncan married in 1679, Lady Harriet Lindsay (circa 1657–1721), daughter of Alexander, Earl of Balcarres, an interesting connection in view of the harper having a presence in Edinburgh and the harp tunes which appear in the Balcarres manuscript. Perhaps having been obtained from this harper, either directly through the family connection, or via the three contemporary Edinburgh music masters, Beck and the two MacLachlans, familiarity with the harper on his visits to the capital.[4]

Sir Duncan Campbell had supported his chief the Earl of Argyle in his rebellion of 1685 and as a result temporally lost his lands which were not restored until 1690,[5] although by that time both he and the lands were heavily indebted as a result of that rebellion. The harper may therefore have had occasions to visit Edinburgh to attend his former patron there, or to play for the Earl of Lauderdale who having obtained under somewhat dubious circumstances the whole lands of Glassary became the major landowner in the area at that period. That the harper and his family from time to time moved between the two homes in Edinburgh and Argyle hints at an alternative source of income.

Carnassarie Castle, where Duncan MacIndeor would have performed. See footnote [5]

Click above to view enlarged image.

Photograph copyright 2016, WireStrungharp.com

In earlier times a plurality of occupations was normal at most levels of society. For example, Edinburgh lawyers, apart from providing legal services for their country clients could often be found making other arrangements and purchases on their behalf. Anyone who travelled on a regular basis could augment their income by buying goods, either on behalf of their friends and relatives at home or on a straight forward commercial basis. An example can be seen in a small collection of deeds recorded by a Glasgow merchant in 1718 but covering the years from 1701 to then. The merchandise was allowed on credit, (the reason for the deed), but those involved apart from other merchants and packmen, included drovers and others who appear to have just been acting for their own people and adding to their own income.[6]

There were a number of people with the name McIndeor in and around Glassary and while some definite links can be made it seems likely that all of them were connected in some way. As family group they owe their name to a forebear having been a Deoradh, the office of a hereditary keeper of a religious relic. In this case the most likely relic was the Kilmichael Glassary Bell–Shrine which was found in 1814 on the farm of Torbhlaren, (Torr A’ Bhlarain). The site lies about a mile north of Kilmichael and just six miles south of Fincharn. The shrine comprises a bell enclosed in a later circa 12th century copper alloy decorated shrine and a recent study of it includes a short discussion of the possible keepers which mentions the fact that there was a family called MacIndeor in Kilmichael Parish.[7]

When the family first come into view they are more closely connected with the neighbouring parish of Kilmartin when in 1534 a Lucas Deor is on record holding Kilchoan. He was followed in 1559 by Michael McLucas Dewar who was still around in 1585, then he in turn was succeeded by Lucas McGillemichael Deor alias McKinichon who received a charter for Kilchoan in 1609.[8] The previously cited study notes the fact that the shrine was found in one parish while the family of dewars

who would normally have held their land in the parish they served should be based in another and queries whether the Mcindeors at Kilchoan and those at Fincharn were the same family.

The cross dealings within the two families suggest that they were connected and the answer may lie in another part of the study which suggests that the condition of the Bell Shrine indicates it was buried not long after it had been made. As the shrine is dated to circa mid 12th century then it would imply that its keepers

the Dewars would have been out of a job well before the changes brought about by the reformation. Time enough for them to have spread elsewhere to find a living including becoming landholders in a neighbouring parish.

If they were indeed originally descended from the same family then an earlier musician who surfaces further east might also be linked especially given the mobility enjoyed by musicians. In any case it demonstrates the sideways movement into other professions that often occurred among the professional families of Gaeldom. This particular example would actually pre–date the reformation when in 1561 Donald Pypar M’Yndoir Pypar bound himself at Strathphillan to make Colin Campbell of Glenorchy his adopted son, a version of the Gaelic custom of Fosterage

.[9]

Main Door. Carnassarie Castle

Click above to view detail.

Photograph copyright 2016, WireStrungharp.com

Returning to the Harper’s family at Fincharn it is possible to link some of those McIndeors on record there together. It is clear from the testament that his brother and proposed tutor

for the children was named Neill and he is first found at Over Fincharn along with a Donald McIndeor in a list of Fencible men made in 1692.[10] Duncan MacIndeor the harper does not feature in this list but that can be explained by the nature of the list, being blind, possibly already of some age or away living in Edinburgh he would have been an unlikely candidate for a military call up. He does though feature along with a John MacIndeor, as one of the seven tenants listed at Fincharne Over

in an action against Sir Duncan Campbell of Auchinbreck issued in 1672. [11]

Panel above door showing arms of Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll and his wife Jean Stewart with Gaelic motto, Dia Le Ua nDuibh[n]e

, (God be with O’Duibhne). The designation O’Duibhne was often used for the head of the Campbell Family.

Click above to view detail.

Photograph copyright 2016, WireStrungharp.com

There was also a Donald MacIndeor listed as one of the three tenants of the two Carrenes

. Now a restored bothy marked on the maps as just Carron

, it is about four miles South of Fincharn at the point where the track and old drove route from Kilneuair having rounded the northern slopes of Sith Mor splits with one branch heading up to Furnace on Loch Fyne while the other continues down to Kilmichael. It is possible that this was the same Donald MacIndeor who appears at Fincharn in the Fencible list and whose wife Margaret Campbell died there in 1695 when Neill MacIndeor became cautioner for the testament.[12] Apart from its implications for the connection of the two Donalds

of 1672 and 1692 this document indirectly also adds to the case that Duncan MacIndeor the harper was blind.

Although her husband Donald was the executor and beneficiary, Margaret Campbell was it would seem fairly wealthy in her own right. After discharging her debts, mainly funeral charges and her years rent, she left stock and grain to the value of £130–6–8. It would therefore appear that while her husband Donald was described as in over Fincharne

she may actually have been the tenant. The Inventory is written by usual record scribe, but the agreement by Neill MacIndeor to act as cautioner for the executor has been added and signed in his own hand. This provides a contrast with his brother Duncan when in a similar position where the harpers agreement was written and attested by a notary, which is understandable if the cautioner was blind and even signing with a cross was ruled out.

Duncan’s involvement dates to three connected records, a testament, inventory and confirmation all dated to 1693 but following on from the death of John MacIndeor in Fincharn who died in September 1688. His testament was given up by his relic Mary Beith in the name off herself and their son Donald. The inventory is couched in similar language but the document is torn and part missing, however the actual inventory is repeated in the confirmation which also has the additional clause making Duncan MacIndeor harper in Argyll

its executor.[13]

The fact that all these Commissary Court Records involving Donald MacIndeor in Fincharn as heir to the estates seem to have a more senior person actually responsible for their execution raises a question regarding Donald. He was clearly old enough to have married, therefore could have been old enough to have been the earlier Donald of 1672. It is possible that he was somewhat feckless in his approach to life and therefore managed by the other members of his family. In terms of the wider family these records also strengthen the probability of a relationship between the MacIndeors at Fincharn and those at Kilchoan as both the harper and John MacIndeor’s testaments show that they had made substantial loans to Lucas MacIndeor and his son Robert at Kilchoan.

The testament of Duncan MacIndeor in 1694 was not the last reference to the harper following his death. On the 11 December 1695 Christian Campbell, described as the widow of the deceast Duncan McIndeor harper in Edinburgh

was ordered by the Inveraray Commissary Court to pay John Campbell, surgeon in Edinburgh the sum of £15–10 shillings. Otherwise she was to be offered accommodation in the Inveraray Tolbooth jail. The debt had accrued as payments for medicines supplied for use of her husband and children and as her share of her husband’s estate would have left her quite capable of paying she presumably felt given the death of her husband and a child that the treatment had failed and she did not have any obligation to pay. But as she does seem to have avoided the Tolbooth Jail, pay up she seems to have done.[14]

While the harper has left these traces of his life in the contemporary records the nature of his music, be it instrumental or song is unrecorded. His possible connections with the harp music in the Balcarres manuscript, either directly through the family or via contact with other musicians when in Edinburgh has been mentioned already, but there is one further likely contact which raises some intriguing questions. Apart from one exception, Duncan MacIndeor is described as a harper in Fincharn or Edinburgh in those records. The exception was the occasion while he was still alive when the notary, on his behalf, added the codicil making him an executor where presumably in his own words he was described as harper in Argyle

defining a working area rather than his actual home.

Although he might have lived at Fincharn and Edinburgh, as a musician he would have moved around and by coincidence there was at that time another member of a professional Gaelic family active in that same area. In 1693 the poet Donnchadh O’Muirgheasain wrote a receipt entirely in Gaelic script for payment by the Earl of Breadalbane for making him a genealogy

.[15] It was written on the back of an account for work which was being undertaken on Castle Kilchurn and seems to have been written and initialled as Booked

by the earl while they were at Kilchurn.[16] This would place the harper and poet at opposite ends of Loch Awe and it seems unlikely that their paths would not have crossed.

Carnassarie Castle. Chimneypiece in great chamber where the harper would have performed.

Click above to view enlarged image. Photograph copyright 2016, WireStrungharp.com

What starts to move this beyond mere coincidence is that subsequent to Duncan MacIndeor’s death, the poet, Donnchadh mac Mhaoldomhnaich O’Muirgheasain later appears composing verse for the MacLeods at Dunvegan, again during a time when there is still a harper, Rory Dall Morison within the vicinity.[17] It is therefore quite possible that this member of a Hiberno–Scottish family of poets was, at least when in Scotland, able to continue having his compositions performed to a harp accompaniment.

There was one further event which possibly adds a post script to the life of Duncan MacIndeor and moves the story into the beginning of the eighteenth century when the Irish Harper Dennis Hampson had commenced his travels. In July 1805 the Rev G V Samson on behalf of Lady Morgan had visited Dennis Hampson and recorded a brief mémoire. It includes some Scottish anecdotes including a visit to Sir James Campbell of Auchinbreck, the son of Duncan MacIndeor’s patron and who would have known his father’s harper in his youth; another about an unnamed family who possessed a harp and a comical story about the Laird of Stone

.

Edward Bunting also quoted this account but with numerous silent changes including changing the date on which Hampson had said Bunting had visited him and turning Stone

into Strone

, a change which does make more sense.[18] Unlike stone

, Strone is a common Scottish placename and there are, or were, two places so named within the Glassary–Kilmartin area. One which is still a farm name today is just eight miles from Fincharn and close to Minard on Loch Fyne. The other was about the same distance west of Fincharn and adjacent to Old Poltalloch, but the name like that of the other MacIndeor home of Kilchoan has been absorbed into the modern Poltalloch Estate and they no longer feature on modern maps.

What is significant about the location is that it would be right where anyone coming from the north of Ireland across to Scotland via Kintyre would pass and uncannily matches the same area where Hampson’s later contemporary Echlin O’Cathain was to leave the most records of his presence in Scotland. It therefore seems likely that Hampson’s anecdote regarding a harp fell within that same area and this raises an intriguing question. The harp was stated to have been a very small one, played formerly by the laird’s father. After he had tuned it with new strings the laird and his lady both were so pleased with his music, that they invited him back in these words Hampson, as soon as you think this child of ours (a boy of three years of age) is fit to learn on his grandfather’s harp, come back to teach him, and you shall not repent it

;– but this he never accomplished.

This last part which appears as a direct quote from Hampson and without the earlier qualification of the laird’s father

is open to to interpretation as the child would have had two grandfathers. If the Rev Samson, or even Hampson himself, had simply jumped to conclusions about which grandfather it had been, then a possibility consistant with the required timespan arises that the lady of the house might have been one of Duncan MacIndeor’s surviving daughters who had inherited her father’s instrument.

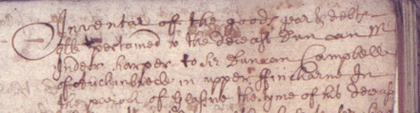

Clipping from the testament.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland. CC2/5/2/57.

Inventar of the goods gear & debts

qlk pertained to the deceast Duncan Mc

Indeor harper to Sir Duncan Campbell

of Auchinbreck in upper ffincharne In

the parioch of Glassrie the tyme of his decease

which was in the month of September 1694

faithfully made and given up be Christian

Campbell his relict ffor herself And in name

of Mary Katharine and Jean McIndeor

and Mc Indeor yr children

And ordaines the said Christian to be yr

overseer during her wideurity and after

her mariadge ordains Neill Mc Indeor

yr uncle to be yr overseer

[1] This is a revised and updated version of an article which first appeared in Notes & Queries of the Society of West Highland and Island Historical Research, Number 30. February 1987. It also now includes by kind permission of the National Records of Scotland a complete transcript of the harpers testament, although any errors in transcription are of course mine.

[2] A list of Auchinbreck tenants of 1672 shows that Fincharn

was let in two parts, Fincharn Over and Fincharn Neither with seven and six tenents

respectively. As these would have been the heads of their families it would indicate two small farmtowns

with at least that number of dwellings. Roy’s map of Scotland sheet 13/3 circa 1747–55 marks both Nether Fincharn and Over Fincharn and the former would seem to be roughly where the modern farm steading of Fincharn is sited. Assuming that Upper Fincharn

of the testament and Over Fincharn

of the map are the same then the harpers home would have been about half a mile north-east of the modern farm building roughly in the vicinity of what is marked on the current Ordnance Survey Maps as a Cup Marked Rock

.

[3] Old Parish Records, Deaths 685/01/0087 Edinburgh. Greyfriars Burying Ground.

[4] Spring Mathew, ed. The Balcarres Lute Book. (2010); Sanger K, Will the right

Common Stock Volume 30. No 1. (June 2013)Mr MacLachlan

please Birl

in his grave

Curiously none of the published commentaries on the Lute Manuscript while agreeing that it was written during the lifetime of Colin, Earl of Balcarres include his sister Lady Henrietta, or his mother Lady Anne Mackenzie, formerly Countess of Balcarres but following the death of her husband, on re–marriage becoming Countess of Argyll, as possible compilers of the manuscript. This omission becomes even more odd when their backgrounds are considered. Both had spent periods in England and on the Continent reflecting the geographical spread of the music represented in the munuscript. While both were experienced writers, Lady Henrietta in fact kept a journal of her life up to 1689. (published in Rev. James Anderson, The Ladies of the Covenant. (1851), pp 502–545, which also includes a biography of her mother the Countess of Argyll).

Lady Anne MacKenzie was born and brought up at a time when the lute would have been the most popular instrument for young ladies. Before the execution of her husband Argyll in 1685 she and her daughters were often at her favourite residence of Argyll’s Lodging

in Stirling and a musical side to their lives is suggested by the presence in three inventories of the furnishings there for 1680 and 1682, of a Harp in the drawing room. Following the failure of Argyll’s rebellion in 1685 when both of Lady Henrietta’s husband Auchinbreck’s homes at Carnassarie and Lochgair were destroyed and Lady Anne MacKenzie’s husband the Earl of Argyll was executed, both ladies became frequent vistors to their former home at Balcarres. Indeed both ladies were at Balcarres when Lady Anne MacKenzie, formerly Countess of Balcares and later of Argyll died in 1711.

[5] Carnassarie Castle was built by Mr John Carswell, post reformation Bishop of the Isles circa 1565–1572 but had come into the possession of the Auchenbreck family by the 1640’s. Since Sir Duncan Campbell and his wife Lady Harriet Lindsay lived there until 1685 then Duncan MacIndeor was likely to have played within its walls. The castle as well as their other home at Lochgair were destroyed by Royalist Forces during Argyle’s Rebellion and do not seem to have been re–built although Sir Duncan claimed compensation for it when he was restored to his lands in 1690.

[6] National Records of Scotland. Books of Council and Session, Durie’s Office, RD3/154. f.292 to f.300

[7] Caldwell D, Kirk S, Markus G, Tate J and Webb S. The Kilmichael Glassary Bell Shrine. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Volume 142, (2012), 201–244

[8] My thanks to Murdo MacDonald former Argyle County Archivist who completed the extraction of MacIndeor records from the Malcolm of Poltalloch papers which I had started before they were transferred from the Scottish Record Office to the care of his archive. Additional copies of the MacIndeor writs can also be found in the National Records of Scotland GD50/184/26/21 and GD50/184/26/39. Thanks also are due to Dr Lorne Campbell for sharing his specific work on the Kilchoan family, private communication 3 June 1987.

[9] National Records of Scotland GD112/24/2. f. 13

[10] MacTavish, D. The Commons of Argyll. (1935), p 38

[11] Macphail, J. R . N. ed. Highland Papers vol 2, Scottish History Society, (1916), p 208

[12] National Records of Scotland. CC2/5/2

[13] National Records of Scotland CC2/3/3, CC2/5/1 and CC2/3/4

[14] National Records of Scotland SC51/7/2/44v – 45r

[15] In an article called The Invention of Tradition, Highland–Style

, published in The Renaissance in Scotland. MacDonald A, Lynch M and Cowan I B, eds, (1994), William Gillies commenting on a Campbell genealogy written by James MacLagan but claimed by him to have originally been by Duncan O’ Muirgheasain suggested that it showed signs of genuinely being copied from a Gaelic excemplar. This evidence that there was such a genealogy adds further weight to Professor Gillies’s argument.

[16] National Records of Scotland. GD170/203/6/45

[17] MacLean–Bristol N, The O’Muirgheasain Bardic Family

. Society of West Highland and Island Historical Research, Notes & Queries. Number VI. (March 1978), pp 3–7;

[18] Stone

does feature in composite placenames as in the Scots Stonefield

but not on its own as a Gaelic name. Strone

on the other hand is a very common geographical placename derived from the Gaelic word srón meaning a nose or projection.

[19] Crown copyright, NRS. CC2/5/2 pages 557–58. Published by kind permission of the National Records of Scotland. The transcription reflects the original as far as possible, including a number of gaps in the text for actual dates of bonds which remained incomplete. There were also a number of errors which had simply been crossed through and in the transcription are indicated by [deleted]

. As with many such testaments the arithmetic was of variable quality as can be seen by the first total made of the assets of £1335 : 06 : 08 Scots which had been corrected to £1337 : 06 : 08 Scots when transferred to the end for the subtraction of the debts of £121 : 01 : 08 Scots.

[20] The Jacobus was an English gold coin worth 25 shillings which was minted in the reign of James VI and I, (from where it got its name, the Latin for James). The guinea was also an English gold coin first minted in 1663 and originally worth 20 shillings, (£1). However, as the values of gold and silver fluctuated against each other the actual value of the gold coins in silver shillings tended to vary. For the purpose of the inventory the actual gold bullion value of the coins appears to have simply been converted into £ Scots.

[21] The surname is unclear and is followed imediately by of divinity

with doctor

then inserted afterwards above the line. Expanding mer

in the following line to read merchant

seems a fairly safe interpretation of that contraction.

Submitted by Keith Sanger, 25 April, 2016

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.