The following descriptive summary is based on observations and notes made on this harp in 2011.

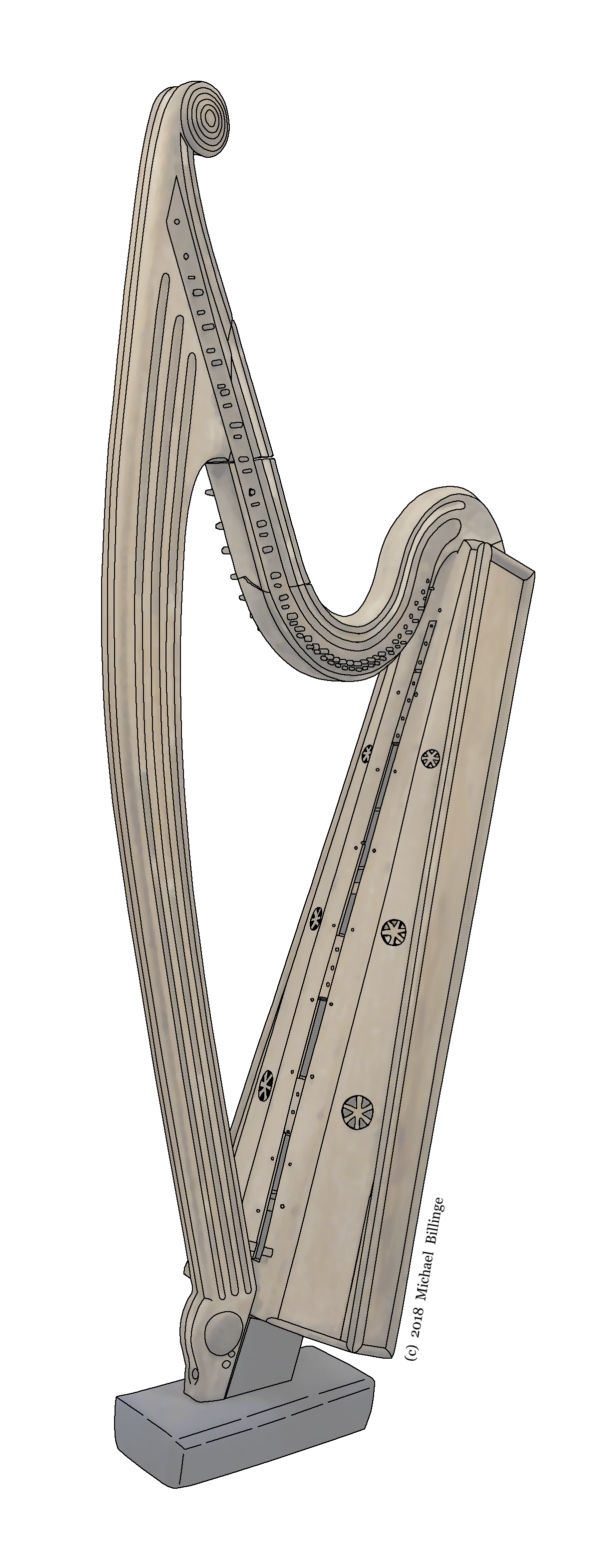

The three-quarter view drawing of the harp

Note: The harp currently stands on a modern weighted base to which the soundbox's projecting block (or 'foot') is attached. Both the base and the projecting block were, at the time of observation, covered in a blue cloth, and this limited further inspection to some extent. I suspect that the projecting block, which is attached and inserted into the bottom end of the soundbox, may not be the original one; but due to the cloth covering, I was unable to form any firm conclusion about this.

Woodwork - All the woodwork of this harp appears to be of pine, or a similar softwood species of timber.

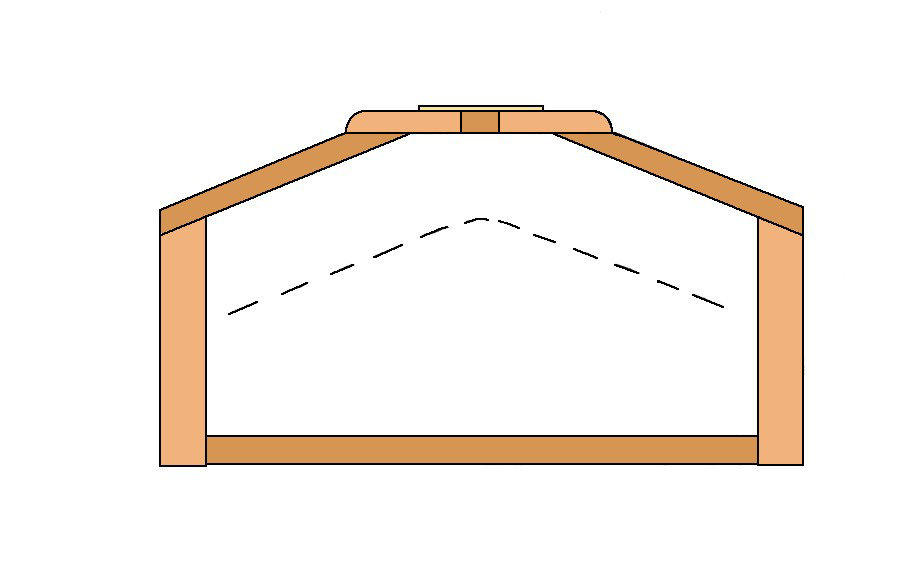

The soundbox is constructed from several pieces of longitudinal grained timber, with the front face or 'soundboard' formed in three facets, the two outer ones being angled at 22½ degrees to the central one. This angle is controlled by the appropriately-formed end pieces (top and bottom) and also a number of lateral ribs attached across the inside of the soundboard. The sides of the box are quite thick, at five-eighths of an inch, whereas the soundboard planks are only five-sixteenths.

A slot has been cut out of the centre part of the soundboard, and a few small iron joining strips (almost like staples) can be seen straddling the gap inside. Into this opening, ten small sections of wood were inserted (as suggested by the evidence). Most of these have since fallen out and are now missing, but a few string holes in the four pieces that remain show where some of the strings were positioned. It seems that these inserts were originally covered by a broad metal strip, for although this too is now gone, the holes left by its attachment fixings are still noticeable.

In the front of the box are three pairs of circular sound-holes, each with a hexafoil shaped insert; and the backboard has three much larger holes, to allow access for stringing. Additional wooden strips are attached along the edges of the sides and ends of the box, which would have provided extra protection for these areas, and they form quite a conspicuous feature.

Indicative cross-section showing main elements of soundbox assembly.

The forepillar is an inch and three-quarters thick, and rises to a circular finial flanked on either side by a decorative disc. These are very slightly domed, were probably made on a lathe, and have been channelled to form five concentric rings. A pair of shallow domed discs are also attached at the lower end, but they have painted decoration rather than rings. Other ornamentation on the pillar includes three carved fluted channels on each side, with another one running over the top of the finial and along the front face. All of this fluting is well formed and cleanly cut.

The bottom end of the pillar is attached to the projecting block of the soundbox, but the exact method of jointing is uncertain. It would seem normal to expect a mortice and tenon joint, but just below the discs there are indications that two dowel pegs passed through the base of the pillar, with another one passing through from the front. This suggests that a different form of structural joint was used; perhaps a mortice was cut into both pillar and projecting block, and a separate piece of wood inserted to join the two. Without being able to see more, I cannot speculate further.

The neck was also cut from timber an inch and three-quarters thick, but since the sweep of this neck is quite deep, two separate pieces of wood had to be joined together to make up the required size. The upper surface is shaped with a curved section, forming a shallow mirrored ogee, with the topmost part being convex. There is also a fluted channel running along each side-face. As with the pillar, all this decorative moulding is well executed.

At the treble end the neck is slotted onto a shaped shoulder piece, which in turn is inserted into the top end of the soundbox. Where it joins the forepillar, a mortice and tenon is used, and the strength of this joint is augmented by the addition of two iron plates running along either side of the neck, which straddle it.

Metalwork (plates) - These plates (or neck-bands) are well formed and matched in shape; and where they are pierced to take the tuning pins, the holes are accurately positioned. [1] Each plate has been cut in one piece from a flat sheet and is fairly substantial, which would have contributed greatly to the structural integrity of the neck. Indeed without them, the neck - formed as it is - would not have been capable of supporting any significant degree of stringing tension.

The plates are fitted into shallow recesses cut into the side of the neck, and the heads of any metal fixings (e.g. nails, through-rivets etc.) were made flat, so that the whole thing sat flush with the side faces. When these were painted over (see below) they would have been virtually invisible.

Metalwork (pins) - The harp still retains 27 of its original 35 copper-alloy tuning pins. These are plain and undecorated, and of a consistent style of manufacture. It seems likely that they are contemporary with the harp, and not salvaged or recycled from an older instrument.

On the left side there is a row of copper-alloy bridge pins beneath the tuning pins, 33 of which still survive in situ. Each one is notched to hold the string in place, and all but the highest pin in the treble are inserted through the metal plate, the exception being positioned directly into the wood just below the plate's lower edge.

Painted finish - The harp was originally covered with a layer of gesso and then painted. Most of this finish has since been stripped away, right back to the bare wood, but traces of the white gesso are still quite noticeable. Patches of the original paint also survive in places, and from this it seems that the harp was predominantly a dark green or blue colour, perhaps some mix of the two. After centuries, it's difficult to determine an exact original shade. There was clearly also some additional decorative embellishment: remnants of line work, picked out in golden-yellow, can still be detected in a few areas.

The use of a gesso base as a foundation for paintwork had two advantages over simply painting directly onto the wood. The first is that the gesso filled in all the little gaps between various sections of the harp, so that cracks or joints were not detectable once the top coat of paint was applied. The second advantage is that the smooth, regular surface provided by the gesso then enabled a high-quality finish to be put onto the final paintwork. Today, stripped to the bare wood, the harp may look somewhat sad; but when new it would have been majestic.

Date of manufacture - Exactly when and how this harp came into the collection of John Hunt [2] is presently unknown. There is no mention of any provenance in the acquisition register, so trying to assess a precise date for this instrument is difficult. The fact that the soundbox is assembled from several pieces of wood - as opposed to being hollowed out of a single block - is little help in refining the date: constructed boxes were being made throughout much of the 18th century, and possibly even back into the 17th.

The use of bridge pins on the neck may seem a relatively late feature, but adding these to control the alignment of the strings is a perfectly practicable idea, which had already become widely used on many other European harps by the middle of the 18th century - and it is unlikely that instrument makers in Ireland would have been unaware of innovations taking place elsewhere. However, the trend for using fluted decoration on the pillars of high-status European examples doesn't appear to have taken off until the 1780s [3] and it may be that the fluting on the Hunt harp's pillar reflects this new fashion. The quality and precision of workmanship seen in the iron plates suggests that they were the product of something more akin to an engineering workshop than a blacksmith's forge, and this in turn may indicate a period when manufacturing in general was beginning to move onto a more industrial basis. Taking all these observations together, the most likely construction date would seem to lie in the late 18th century, or perhaps the early 19th.

Historical significance - This potential dating straddles two interesting eras, the first being when wire-strung harp playing was in decline, and the second when attempts were beginning to be made to revive it. Since this instrument was clearly not intended to endure the rough treatment that an itinerant musician's life on the road inflicted, it indicates that at the time it was built, there was still a market for a new high-quality wire-strung harp.

Assuming that the Hunt originated in the 18th century, this now brings the number of harps with constructed soundboxes that survive from this period to seven (Hollybrook, O'Conor-Carolan at Clonalis House, Kearney No.1 & No.2, Reverend Best, Victoria & Albert Museum, and Hunt). This figure is significant, because it is greater than the number of extant harps from the same era that have hollowed-out soundboxes (i.e., six: Sirr, Downhill, Bunworth, Mulagh, Belfast-O'Neill, and Royal Irish Academy No.2). There is a popular belief that one of the key characteristics of the "real" Irish wire-strung harp is that the soundbox had to be hollowed out of a single block of wood. But when it comes to the great period of Irish harping - the time of Carolan and his like - reality has shown that this is simply not the case.

On the other hand, should anyone consider it more likely that the Hunt harp was built in the early 19th century, this too is an interesting conjecture; for it would demonstrate that a continuous tradition of wire-strung harp making persisted in Ireland for longer than was previously thought. The Hunt harp's style of construction certainly predates the methods developed by John Egan and other wire-strung harp makers during and after the second decade of the 19th century.

Either way, this instrument occupies an important position in the panoply of Irish historical harps; and as such, it should not be dismissed as some mere anomaly.

[1] The quality of manufacture of these plates is far superior to that found on other harps which used iron for their neck-bands. For example, those found on the Hollybrook and Royal Irish Academy No. 2 harps, which were probably formed at a blacksmith's forge, are much rougher in shape, with the positions of their tuning pin holes wandering in an irregular fashion (the neck-bands of the RIA No. 2 are particularly crude.)

[2] John Hunt died in 1976, and his son (also called John), who presented the harp to the museum, followed in 2004. For a detailed account of the life of this most interesting 20th-century antiquarian, see:

Brian O'Connell, John Hunt: The Man, The Medievalist, The Connoisseur, O'Brien Press, 2014.

[3] Some fine examples of these may be found in the collections of The Cité Museum, Paris; The Palais Lascaris, Nice; and The Musical Instrument Museum, Brussels.

Submitted by Michael Billinge, April, 2021

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.