Robert Bruce Armstrong included this harp in his work (at pages 107–109) on the basis that it had already been included among James Drummond’s illustrations published in 1881.[1] He then goes on to suggest that it was a poorly made reproduction of the Hempson or Downhill harp. While clearly influenced by the design of the Downhill instrument, the suggestion that it is just a poor

reproduction cannot be allowed to stand as this harp was clearly a well proportioned instrument in its own right.

Picture from 'Ancient Scottish Weapons'

by James Drummond, 1881

Both Armstrong’s and Drummond’s books provide measurements. In the case of the latter, as it was a posthumous production (James Drummond having died in 1877) they were provided by that book’s editor Joseph Anderson, the Keeper of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland. The measurements on the whole agree with each other although differing slightly in a few areas, differences which can be reconciled if it is assumed that they were measuring from slightly different points on the harp. Based on the argument that it was likely to have been strung during a period when the Irish harp was in use, Armstrong goes on to give all the string gauges and some string lengths, except for the gauge of the 14th string which was said to be missing.

For the background history of this harp, R B Armstrong mainly drew on the catalogue for an exhibition in Belfast in 1852 where it was listed as the harp of O’Kelly restored

and a statement in the appendix that:

The Clarsach or Harp of O’Kelly was presented by Mr Kelly of Barleyfields, near Dundalk, to Mr Peter Collins, a well known violinist. It fell into the possession of the present owner [John Bell] in 1812.

Armstrong then goes into some discussion regarding the owner, Mr John Bell, including the suggestion that the date of 1812, when Bell was said to have acquired the harp, was a mistake. In fact Armstrong’s account itself can be shown to be incorrect in a number of details, including the date he gives for Bell’s death.

John Bell died at Dungannon in 1860 and was buried in the Drumcoo Cemetery where his grave stone which was erected by his brothers Thomas Allan & Christopher Bell of Abbots Haugh, Falkirk, has the inscription that:–

John Bell, M.R.I.A; F.R.S &c. Second Son of John Bell of Lyon Thorn, & Bell’s Park, Camelon, Stirlingshire. N.B. Born at Camelon 1793. Died Dungannon 1860. Known for his Antiquarian Researches & Collections in Connection with Ireland.[2]

If the date of Bell’s birth given on his gravestone was correct then he would only have been 19 years of age when having moved to Ireland he acquired the harp in 1812 and Armstrong’s doubts about that date would be more acceptable. However, somewhere along the lines of communication in the making of the gravestone something went astray as he was not born in 1793. His parents were John Bell, a Tea Merchant[3] and Marion Cuthill and they had a number of children including Christopher born in 1788 and Thomas Allan born in 1797. The only John in the birth records for that couple was actually recorded on the 4 July 1786 therefore making him a much more likely 26 years of age when he acquired the harp.[4]

He was certainly in Ireland before 1812 when he is on record in Newry described as a landscape painter and already showing an interest in the study of Irish antiquities and was said in a contemporary account to have opened upwards of 60 different cairns

by 1815.[5] Although mainly earning his living through practising and teaching art, his antiquarian pursuits also seemed to have occupied a considerable part of his time. His publications were prolific and he put to use both his artistic and very competent draughtsmanship skills in recording all the antiquities he visited.[6]

When in 1852 the British Association for the Advancement of Science held their twenty–second meeting in Belfast, John Bell was actively involved in arranging the Collection of Antiquities and other objects Illustrative of Irish History

exhibited in the museum in Belfast. The exhibits were mostly provided by private collectors and Bell’s own contribution was one of the largest of these. He was also involved in the compilation of the exhibition catalogue, so would certainly have been able to ensure that the descriptions of the items he had loaned from his own collection were accurate.

The catalogue groups the exhibits under the names of the donors, but some items were actually displayed separately around the walls of the rooms, hence the harp features twice. Once in the main section listing all Bell’s exhibits where it is listed as The Harp of O’Kelly, restored

, and secondly in a section devoted to all the harps on display where it is described as Harp, a restoration of the Harp of O’Kelly, (From J. Bell, Esq, Dungannon)

. At the end of the catalogue there are a number of notes relating to some of the exhibits and it is here that it is stated under Harps–

TheClarshach, or harp of O’Kellywas presented by Mr KELLY of Barleyfields, near Dundalk, to Mr PETER COLLIN, a well known Violinist. It fell into the possession of the present owner in 1812.

...which is a fairly definitive statement with no hesitation surrounding the date.[7]

Bell seems to have taken a special interest in harps and harpers judging by one of his surviving notebooks. Indeed he seems to have tried to obtain another through the offices of the harper Patrick Byrne whose concert in Dungannon he had attended in 1849. His jottings contain a more expansive version of the description in the exhibition catalogue:–

Joseph Kelly of Barleyfields Esq, near Dundalk gave my harp to Peter Collins, when a boy he used to ride through the house on the harp with his handkerchief in its mouth as a horse.[8]

This statement is a little ambiguous, who was a boy, Peter Collins or Joseph Kelly? But either way it suggests that the harp may date back to the eighteenth century.

Although John Bell was married in October 1830 to Mary, only daughter of Mr Charles McClelland of Loughgal, Co Armagh, there seem to have been no direct heirs of that marriage and on Bell’s death his collection, including the harp, passed to his remaining relatives in Scotland. They in turn sold the collection to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1867 for what was described as a fair price

£500 provided through a special grant from the British Treasury.[9] According to the museum catalogue published in 1892 the Bell Harp

catalogued as LU 2 was being exhibited in the same display case as a cast of the Trinity College Harp which had been donated by Robert Glen in 1881, catalogued as LU 1.[10]

When in 1980 a request was made to see these two harps which do not appear to have been on public display for some years it produced the response that while I was welcome to view the Trinity cast, the Bell Harp was indeed said to be in the museum, but it was the first time in that writer’s experience of some 30 years in the museum that it had been asked for and he was at a loss to know what had happened to it. In further conversation during the follow–up visit to the museum it was suggested that as there were plans in progress for a major re–arrangement of the museum storage and service buildings there was a very faint chance it might turn up during the moves.[11]

A further enquiry was therefore made in 1991 and it was confirmed that the Bell Harp

was definitely missing and appears to have been removed from the collection some years ago

.[12] This in turn led to an attempt to trace what had happened to it, starting with searching the archives of the Society of Antiquaries from the year 1904, when it was last known to have definitely been there when Armstrong had examined it for his work.[13] Although no direct reference to the harp was found it has been possible to reconstruct the circumstances which probably led to its loss.

At the beginning of 1914 the museum was completely emptied of all its contents in preparation for some major up–grading work involving fire proofing and re–flooring. Some space for storing the collections was loaned by the other side

of the building used by the Portrait Gallery, but it is clear from the minutes of later meetings that the national collections remain lost to the public, for the time being in the safes, cellars, etc., to which they were consigned in 1914

.[14] In the hand written minutes of the meeting following the clearance the chairman thanked those who were involved in storing the exhibits, but there is no indication that a list of where the items were stored was made, or if one was it has not survived.

Of course given the social norms of that period involving a society of gentlemen and that the storage was only expected to last about a year, it may not have been felt necessary to compile a list. No–one at that point would have anticipated that everything was about to be overtaken by the out break of the war. However that stopped any of the upgrading work almost before it had started. This was compounded by the now cleared museum building being taken over by the wartime Timber Department of the Board of Trade. It was not until 1919 that the society received the building back and work could recommence. The work was however, slow in completion due to the immediate post–war problems including ironically, given the museums temporary use, a shortage of timber for the new floors.

It took until 1921 before the work was completed and the exhibits began to be returned to the new display cases before the museum was re–opened to the public in January 1922. During that period from 1914 to 1921 not only had the museum been closed but there had been a considerable change of staff. Joseph Anderson who had seen Drummond’s work with its illustration of the Bell Harp into publication and might have been expected to remember that harp when the museum reopened; had retired as director of the museum just before it had closed in 1914 and died in 1916, thereby removing any chance of continuity. Other younger staff had been lost through the war as had a number of the society members, while as in any period of time natural removal through death had taken its toll on the membership in any case.

There had been a further event which might also have had an impact when the exhibits were finally being returned to the display cases. The Lamont Harp which for a long time had been on loan to the museum had been removed when it was purchased by a private buyer when sold by its original owners in 1904. It was though returned to the museum as a legacy following the death of its purchaser, Mr Moir Bryce at his death in 1919. As result although probably two harps, the Queen Mary and Bell had been removed to storage when the museum was emptied in 1914, two harps, but now the Queen Mary and Lamont, were restored to the new displays; the Bell Harp being overlooked and remaining wherever it had been stored.

If that was the case, then with the time which had already past through the period of the war, compounded by a failure to reclaim the harp afterwards would have, with the further passing of time, led to its original temporary curators

losing any recollection of why they had it, or that it was not really theirs. With that scenario two harps which subsequently appeared at auctions just a few years before the outbreak of the second world war are of interest. The one with the weakest potential claim was advertised as among the items for auction by the Edinburgh company, Dowell’s Ltd in their sale on the 25th November 1938 and was described as an Antique Irish Harp

.[15]

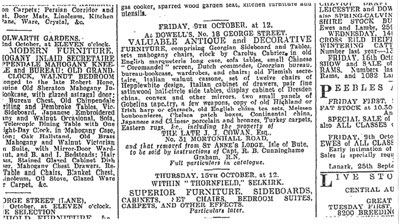

Advert of the auction for the (possible) Bell Harp [You may click on the picture to view a detail of the harp description]

However, about two years before that a harp whose description was an even better fit with the Bell Harp was included in an earlier auction by Dowell Ltd when on the 26th September 1936 an advert for the forthcoming auction to be held on the 9th October, included what was described as copy of old Highland or Irish harp or clarsach

. It was part of a collection of Valuable Antique and Decorative Furniture, the property of the Late J. J. Cowan Esq of No 31 Mortonhall Road, Edinburgh.[16] Oddly neither the sale catalogue or more importantly Dowell’s sale record book for the day of the auction make any reference to the harp,[17] suggesting that it had either been sold privately before the auction, or possibly withdrawn from sale.

John James Cowan was a member of the wealthy papermaking family who owned the Valleyfield Mill at Penicuik. He was a noted collector of artworks and according to his testament had left the contents of his house up to a certain value to be chosen by his daughter with the rest to be sold by auction or private bargain as the trustees thought expedient.[18] Attempts to further trace the instrument have been unsuccessful, but whether it was the Bell harp or not, what does seem likely is that the Bell harp was never returned to the museum after its original removal and as it has never re–surfaced since was probably a casualty of the extensive damage to property which occurred during the Second World War.

From the archives of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, now the National Museums of Scotland used by permission. [You may click on the picture to view a close–up of the harp]

Although the original harp probably no longer survives, apart from Drummond’s illustration, there are two photographs of the harp still in existence. Even more fortunate, although taken at different times they provide a view of each side of the harp. These taken together with a recently found painting of another lost harp[19] does suggest that the Bell Harp

fits into the style of harps made by members of the O’Kelly family of harp makers. The earliest of these photographs is among the archives of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and shows the harp standing between two chairs with the soundbox to the left hand side and the pillar to the right as seen by the viewer. It is not clear why the chairs and a Highland Bagpipe draped over one of them were included, other than perhaps to create an artistic tone

to the picture.

The picture is mounted and the surrounding margin includes two labels. One completely in Latin identifies it as coming from the Bell Collection while the other describes it as the Harp of O’Neill the last of Irelands Citheredian Minstrels

. Since this claim was never made by John Bell himself it must be treated with some circumspection as an example of spurious antiquarian labelling.

The second picture showing the other side of the harp was found among the various inserts in R B Armstrong’s own copy of his work on the Irish and Highland Harps, now in the collections of the Royal Irish Academy (MS 23 G 35). Although it is not labelled and has suffered deterioration at some point from over exposure, probably to sunlight, it was immediately recognised by Michael Billinge as being of the Bell Harp. Subsequent investigation has shown that it was taken by Alex A Inglis, an Edinburgh photographer used by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.[20] The National Museum of Scotland library still holds some photographs of the Queen Mary and Lamont Harps taken by the same photographer.

This photograph of the Inglis photograph of the Bell harp (by permission of the Royal Irish Academy ©RIA) was taken by Michael Billinge, ©2014. It is seen propped up against Armstrong’s personal copy of The Irish and the Highland Harps in the Library of the Royal Irish Academy MS 23 G 35.

Cross–reference link to where this photo is included in the catalog of Armstrong’s papers.

When placed together the pictures do present one mystery. Armstrong in his description of the harp made the point that it had strings on it and as he puts it:–

As this instrument was made, and the strings probably supplied, at a period when the Irish Harp was in use, the following gauge measurements, etc, may be of value.

He then proceeds to give a list of string lengths, material and gauges. In the earlier photograph there are some broken strings visible and it is quite possible that there were more short lengths attached to the ends of the tuning pins on the side of the harp facing away from the camera. However the later photograph of the other side of the harp taken by Alex Inglis indicates this was no longer the case.

Unfortunately there is no firm date for this later picture although it is mounted on a card with the business stamp of Alex A Inglis on the back. Inglis died on the 20th May 1903,[21] but while this might place an at the latest

date on the picture it should be noted that his son, Francis C Inglis carried on the business from the same studio and might initially have continued using his father’s stamp. It does seem likely that the photograph was among the last examples of the father’s work and might have been intended for Armstrong’s publication which must have been in preparation prior to the date of the photographer’s death.

Since there must have been some wire strings, or at least parts of them, still attached to the instrument when Armstrong made his measurements of the string gauges, (it would not have needed to have been strung for him to obtain the string lengths from soundboard to pin); it is possible that they were removed to tidy up the harp for the photograph. Even in those more cavalier times this desecration of an historical artefact might have raised eyebrows and if not authorised by Armstrong could well account for him not in fact using the picture.

[1] Drummond, James. Ancient Scottish Weapons, a series of drawings by James Drummond With introduction and descriptive notes by Joseph Anderson, Keeper of the National Museum of Antiquaries of Scotland. (1881). The description facing Plate LI, – Irish Harp reads; –

This Irish Harp, formerly in the collection of the late Mr John Bell, Dungannon, is now in the National Museum of Antiquities, Edinburgh. It measures in extreme length 3 feet 8½ inches, and in extreme width 2 feet 8½ inches. The body of the instrument, or sounding–box, measures 3 feet 2 inches in length. 3½ inches in breadth at the top, and 11 inches in breadth at the bottom, and is 3 inches deep throughout. The upper arm of the harp measures 27½ inches in extreme length, and terminates in front in the head of an animal. The fore–arm, or bow of the harp, measurers 3 feet 10½ inches in length. The median line of the sounding-box is pierced for thirty–four strings, and the string-holes have triangular mountings of brass. The upper arm of the harp is strengthened by bars of metal on either side, pierced by holes for thirty–four pins. The sides of the body of the instrument are ornamented by a single wavy line carved in relief, and the six sounding holes are filled with a geometric ornament.

[2] lot Information, Drumcoo Cemetery, 3 Oaks Rd, Dungannon.

[3] According to the details of his father given in the Statutory Death Record of Thomas Allan Bell, GROS 479/020066

[4] GROS OPR Births, numbers

[5] Haworth, R. G. John Bell of Dungannon 1793–1861. Ulster Local Studies, (1981–82) Volume 7 number 1 and volume 8 number 1. Part one pages 1 to 10 and Part 2 pages 10 to 19.

Once more there is a curious discrepancy with his dates, the author of this article giving Bell’s date of death as the 21st of January 1861, though also having reservations about the gravestone birthdate of 1793.

[6] Haworth, R. G, (1981–82) see note 5

[7] Descriptive catalogue of the collection of antiquities, and other objects, illustrative of Irish history, exhibited in the museum, Belfast, on the occasion of the twenty–second meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, September, 1852. Published by Archer & Sons, Belfast for the Belfast Museum. (1852).

[8] Farmer, Henry George, Some Notes on the Irish Harp, Music and Letters. Volume 24, (1943), 104. The original notebook is now among the collections of the University of Glasgow, MS Farmer 332.

[9] Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Volume 8 (1868–69), p 4

[10] Catalogue of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland. (1892), p 317

[11] Letter from Stuart Maxwell, National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland. 27 June 1980.

[12] Letter from J Moran, National Museums of Scotland. 22 January 1991.

[13] My thanks to Morven Donald, Library and Information Assistant, N M S. for her patience under difficult circumstances at that time when the main library was undergoing renovation, for keeping the flow of minute books and other relevant archive material coming.

[14] Anniversary Meeting of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. In Volume 53 (1918-19), of the Proceedings page 7.

[15] The Scotsman, 24 November 1938, Classified ads for Dowell’s Lt, Auctioneers and Valutions. The harp was accompanied by a Rare Old Highland Targe

. Although other items from that days sale are listed in the sale catalogue and record book neither the harp or targe were included. (National Library of Scotland, Accession 7603, Records of Dowell’s Ltd).

[16] The Scotsman 26 September 1936.

[17] National Library of Scotland, Accession 7603

[18] National Archives of Scotland RD5/1963/3637 folios 14–18

[19] Please follow this link to the Maguiness Page hosted here on WireStrungharp.com

[20] Alexander Adam Inglis was born in Aberdeen but had moved to Edinburgh by the time of the 1881 census. Described primarily as a Landscape & Architectural Photographer

; he was another in a line of photographers who lived and worked from the studio at Rock House, Carlton Hill, which had originally been the base of the photographic pioneers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, better known in harp terms for the series of portraits they made of the Irish Harper Patrick Byrne.

[21] Statutory Deaths 685/03 0291

Submitted by Keith Sanger, 10 July, 2016

The image from the Royal Irish Academy is reproduced by permission from their collection, identified as Bell Harp from MS 23 G 35. This is the harp and book photo.

The National Museum of Scotland’s photo is the one with the pipes and chairs. It comes from the archives of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and is reproduced by permission

The Bell & Book photograph was taken by M. Billinge of the Inglis photograph propped against Armstrong's own copy of The Irish and Highland Harps, both of which are in the collection of the Royal Irish Academy, reproduced here courtesy of the RIA.

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.