Originally a lecture presented on 12 June 2011 at the Gaelic Harp Festival on the Bunworth Harp replication commissioned by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusettes, this paper was later published in the March 2012 Wire Strings newsletter of the Wire Branch of Commun na Clarsach under the title The Harp of Kilcoy Castle. By republishing it on WireStrungharp.com we do not intend to promote the Kilcoy above any other well–made small wirestrung harp. The author chose the Kilcoy for her discussion in Boston as it was the small harp with which she was most familiar.

The Boston Conservatory photograph by Cynthia Cathcart

In the summer of 2011 the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston presented the final piece in a long–range project: a replica of the Bunworth Harp, an historic harp bearing the date 1734 and owned by the Museum as part of the Leslie Lindsey Mason Collection. This occasion was the inspiration for a symposium on the wire–strung harp tradition of Ireland and Scotland, which was hosted under the direction of Nancy Hurrell at the Boston Conservatory on June 11 and 12, 2011.

The symposium thus revolved around the making of replica harps and the study of those that survive from the past. The highlight of the weekend was the showing and playing of the replica of the Bunworth harp with the original standing as an honored guest to one side of the stage. Prior to this concert, a series of lectures were given at the Conservatory on subjects such as the rudiments of measuring an historic harp, ways of determining the building techniques, and even locating old harps from which copies may be made. I was asked to deliver the final lecture of the symposium, on the topic making historical harp replicas today

with a focus on the popular 19–string Kilcoy harp made by Ardival Harps of Strathpeffer, Scotland. Following is a write–up of the talk I gave.

Ardival Harps is a Scottish company making historical and traditional harps, established in 1993. The company’s aim is to produce a variety of instruments that reflect the type of harps that have been played in Scotland for the past millennium. The mission is to create instruments of sound craftsmanship that give people an opportunity to explore the sounds of harps of the past.

The Kilcoy harp is surely Ardival’s most popular model. It is a small harp, standing just under 24 inches tall, weighing a slim 3 to 4 pounds, strung with 19 brass strings. Its size allows it to fit in the overhead of most airplanes, yet it can handle just about any kind of music you might want to play on it.

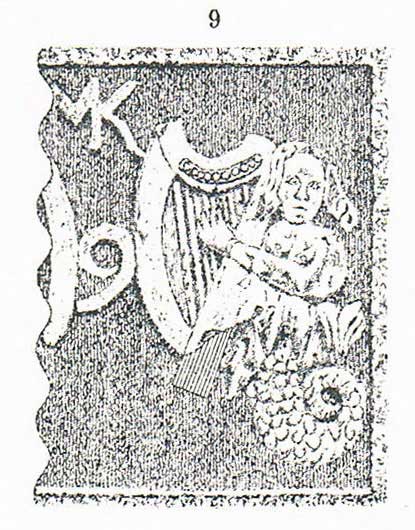

The harp takes its name from Kilcoy Castle, a tower house located about eight miles from Inverness at the western end of the Black Isle. The tower was probably built soon after the land was acquired in 1618 by Alexander MacKenzie. Inside there is an ornate fireplace lintel dated 1679, on which two mermaids are represented, each playing a small harp.[1] The carvings are each a little unique, as if they were individuals and not just a design feature.

The Kilcoy is copied from one of those harps. But despite this honourable pedigree, it fails the replica

test for some people.

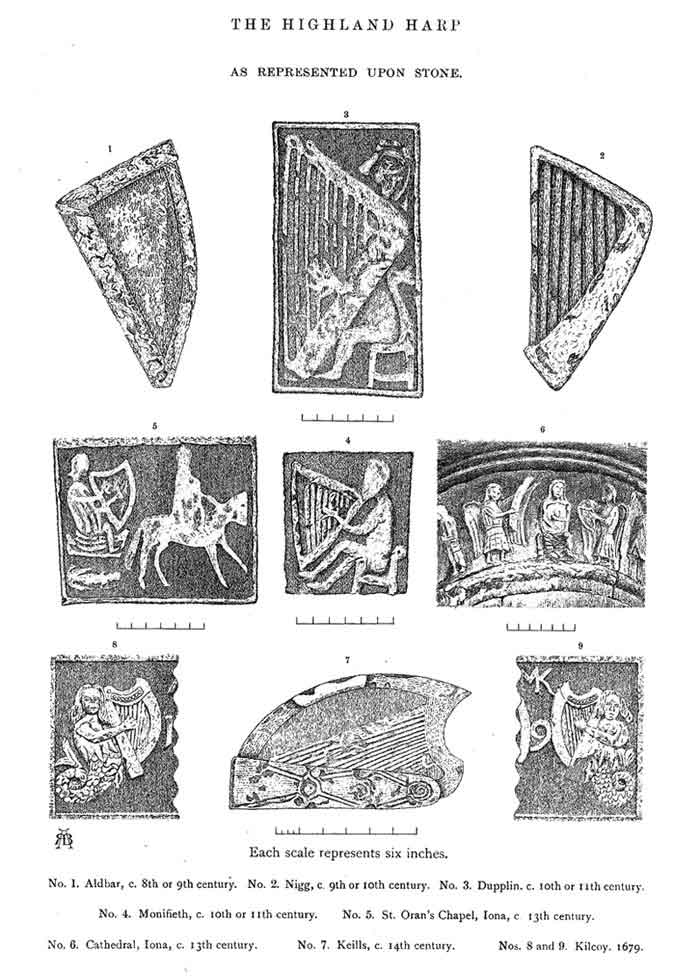

Illustration of the plate facing page 154 in The Highland Harp by Robert Bruce Armstrong [2]

Zan Dunn, owner of Ardival Harps, refers to the historical replica harps as confirmational copies.

We learn from these copies of historical harps, gathering facts and indeed gathering scientific data, confirming (or not) our thoughts and ideas about the instrument.

One thing that emerges as we look at the extant harps is that, just like the mermaids’ harps on the fireplace, no two are the same.[3] Replication is a modern idea, probably coming from a conformist, industrial–era ethos where we expect the products of a factory to all have the same specifications.

When making a precise replica what exactly do we replicate? If the harp we want to copy has been repaired in the past, do we replicate the repairs? Or do we try to make the harp as it may have looked before the damage occurred? Do we try and correct the design error that led to the failure? How do we make that correction? Might we learn more by making the copy as it was so we can observe it failing? Can we tell what it looked like prior to the repair? What do we do if it appears that a part was replaced after the harp originally left its maker?

Do we copy the broken harps? If I’m making a copy of a broken harp, but I make it so it’s not broken, is it still a copy? I remember seeing an American Colonial style sideboard in a nice furniture store a few years ago. One of its doors was broken, the wood was split completely through. I found a salesman and said,Do you know that there is a broken piece of furniture on your sales floor?

and he said, Oh, that’s one of our Williamsburg replicas. The original was broken, so that’s how it was copied.

My response was, “so do you sell many of those?”

One of the other lectures at the Boston symposium was a review of one–thousand years of history for the wire–strung harp. But the oldest harp we have is the Trinity College harp, and the Trinity College Library dates it to 1500. This leaves us ignoring half the harp’s assumed history. What about the harps from earlier than 1500? Can we create those, from other evidence we have, and call them replicas?

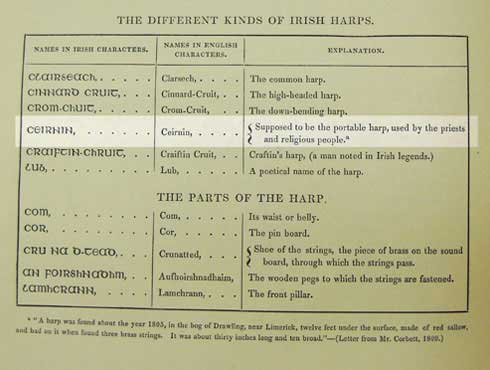

The Bunting definition of Cerinin; however, no other source suggests this usage. The RIA Irish Dictionary, which cites examples of all this word’s inclusion in Irish manuscripts, does not include any reference using this definition of small harp

. Thus this definition from Bunting is suspect.

The harps that have survived are all large harps, does this mean we can only replicate large harps because that’s all we have to look at? But looking at the illustration which includes the Kilcoy mermaids in Robert Bruce Armstrong’s book, we can observe that two of the other illustrations on that same plate show small harps, each sitting in the player’s lap. And those are only there by chance, that plate was not meant to be an illustration of small harps. Some will suggest that images of small harps were drawn out of proportion, but this begs the question of why sometimes the harps were drawn large.

Further historical evidence of small harps can be found in Edward Bunting’s Ancient Music of Ireland [4], in his General Vocabulary of Ancient Irish Musical Terms he gives two words with the meaning “harp” (cruit and clairseach) and the word ceirnin for small portable harp.[5] It would seem that small, portable harps have been around for awhile, else why have a name for them?

Is it even possible to make an exact copy of an instrument? No two Kilcoys are the same, even though Ardival knows precisely how they’re made; they own the original plans! Each one is made the same way, and yet each one sounds and feels different. One may weigh a little more than the next one. If we can’t copy these known harps, with their known measurements and types of wood (and we even know how the wood is prepared from tree to workshop), how can we even hope to make exact

copies of harps for which we have no plans and in many cases are far from certain what the wood is?

If we can follow the essence of the wire–strung clàrsach, conforming with the evidence of descriptions, carvings, paintings, and so forth, we are surely building historically informed instruments. Are these not replications?

We might also want to consider the harps that did not survive because they lacked beautiful decorations, or had not the appeal of belonging to a wealthy family or a well–known harper. Consider Denis Hempson’s Downhill harp. A fine instrument, but did it survive because it was a truly outstanding instrument, among the best ever built, or merely because it belonged to Denis Hempson?

Perhaps an example from another instrument can help. Consider the guitars of Stradivarius. Following is a quote from a book on those historic guitars:

...up to now the only known guitars of the

classicalperiod of Cremona’s stringed instrument makers are those of Stradivari, and Bellow [a scholar whose work Gregori has been discussing previously in the text] maintained that their distinguishing feature, in marked contrast to the decorated guitars of his contemporaries, isa classic restraint and elegance equaled only by modern luthiers.In my opinion, however, he did not bear in mind the instruments shown in many paintings of the period […] These make one think that there must have been a great many guitars made for

real musicians, but because they did not have the exuberant decorations of the artistic pieces for thesalottothey were more likely to be destroyed. In this way, thepreciousinstruments have come down to us in greater numbers, and theordinaryones are rarer. Stradivari’s have survived by pure chance, maybe only because they still existed when the prestige of their maker’s name began to titillate the market.[6]

If only some maker of wire–strung clàrsachs had earned more prestige during their lifetimes, we might have more harps to copy!

It’s time for a story. There was a woman who had a special recipe for baked ham, part of which was to slice an end off each side of the ham. One day she was preparing a ham while her mother was in the kitchen. As she sliced the ends off the ham, her mother asked why. The younger woman said, You taught me to do it this way!

Her mother replied, But you have a full–sized oven! I only cut the ends off because we had such a small oven and that was the only way it would fit.

When we make a measured replica, might we be cutting the ends off the ham?

Rather than copying the last harp he made, a harpmaker would be more likely to take the wood at hand, and make a harp of the size possible from that piece of wood. Perhaps he would make it smaller, but he most certainly would not make it any bigger than the wood he had to work with. He would make the harp informed by his experience, and probably to the requirements of the musician for whom he was making it.

Replication yields facts, but as Susan Hellouer of Anonymous IV has said, you can’t sing a footnote.

[7] The harp is meant to be played! Certainly some luthiers are making copies solely for study, to see if a design works or to experiment with materials or building techniques. A harper may or may not be involved in that process. But for most of us, the intention is to play it.

Are we making these replicas for the makers? Must a professional harper perform solely on a replica harp to be taken seriously? Can a person who simply likes the sound of metal strings have an instrument that is not a precise replica and still be accepted as playing a legitimate instrument?

What about our audience? The people who are going to listen to the music played on these harps. Is it necessary that we perform on measured replica harps to duplicate the sound of the original music? Sounds that enter our ears are perceived differently today than they were in the past. Even if we could make a perfectly accurate reproduction, even if the sound waves are exactly the same as in days of yore, our experience of those sounds will be different. It’s different now!

There are many ways in which sound is different for the modern person.

Our perception and, probably more significantly, our expectation of low tones is affected by our experience of sub–woofers and electronically enhanced bass. Our attitudes towards the balance between treble and bass is affected by stereo systems in our homes and cars that allow us to change that balance, to bring up the bass or the middle–range if we like, at the turn of a knob.

What will be the ultimate effect of MP3 compression on our perception of music? As we digitally compress musical sound, thus reducing or even eliminating the upper harmonics so we can fit more music on our digital storage devices, what is happening to our perception of those upper harmonics, sounds that are so important to the sound of the wire–strung clàrsach?

We can’t unlisten

to the big harmonies we have heard all our lives. Our familiarity with modern harmonies changes how we hear a simple melody line. We feel that something is missing, we think we need to add chords.

And what of tuning! How are our expectations of tuning affected by the electronic instruments in our experience that are always perfectly in tune? Our modern ears are constantly exposed to Equal Temperament, to A=440Hz. Some of us try mightily to avoid exposing our ears to this, we shut off the radio and re-tune our harps, and good for us! But we don't have ear–lids

— if we’re in an elevator or shopping mall and music is being piped in, we are powerless to stop it.

Everyone learns to screen out sounds. This was true in times past as well. We screen out the clapping mechanisms on instruments, the wobble of a wolf tone

, the click of nails on a string. But some of the sounds we have to screen out today are quite different from times past. There are blowers from the furnace, electric fans, the sound of traffic on the street, airplanes and helicopters overhead, the faint scream of electricity in our walls. A further noise to ignore is the frequency of your cell phone’s ring sounding in the tones of the music you hear. Is that your cell phone going off, or the B

string of the harp being played?

The modern audience has become accustomed to virtuoso performances. Perfection is expected. Concerts were an innovation of the 17th century[8], yet how many of us attend concerts expecting perfect performances of medieval music on historic instruments?

These modern expectations of performance also mean that if I am not busy with both my hands, my audience may conclude that I’m not very good. Years ago, when I was still playing in competitions, I received a judges sheet critical of the fact that I had not played enough chords. The judge wrote that I needed to find more for my bass hand to do. She also gave me first place. The music was good, it just did not fit her modern expectations of performance practice.[9]

Is it the sound waves hitting our ears that define music? Isn’t music about the emotions and feelings that are aroused in an audience? How is the meaning delivered to the listener? What of a perfectly shaped phrase, the contrast of dynamics and articulation? Must a harp today sound just like one in the past to achieve the goal of the performance, or is there something more important?

In our past, music accompanied events. The musical context of the event was critical. A Salutation would be played as someone of importance, the host or a guest of honor, entered the room. The harper begins playing the salutation, and everyone in the room turns or perhaps even stands to better see and honor the person entering the room. Yet when a salutation is played in a concert, the audience keeps their eyes on the stage, on the “performer”, and to look at the door in the back of the hall would be consider quite improper.

In recent years much focus has been concentrated on the physical instruments. And this should probably continue. But it must be tempered with the goal of replicating the experience of the music.

We have chosen this instrument for the special sound that wire strings make. We have all been drawn to the bell–like ring, the music, the long tradition. So we copy of the design that gives the ringing which needs to be damped, a sustain that encourages fewer notes in our arrangements, the smaller range required of the tension of wire strings that forces us to use our imagination, some of us even limit ourselves to music that pre–dates some significant point in the past. This is all good.

It is limitations that give us the room to be creative.

Many of us love these instruments for the social history that informs the music. The music gives us a structure upon which to memorize dates and names from history. The study of the harp gives us a chance to research and enjoy wearing clothing appropriate to the era our music of choice comes from. Perhaps the culture of the music we play encourages us to take the appropriate language lessons, expand our skills to include singing or reciting of poetry.

We might use the opportunity of the music we play to learn more about those events that the music would have accompanied in times past. We better understand how these events have changed through the lens of the music. Consider the performance of a lament. I play a lament in a concert and at its conclusion everyone applauds (assuming I played it well). Yet when I played a lament at my grandmother’s funeral everyone wept. Experiences like this can lead us to new understandings of times past as well as times present.

Our historic harps also guide us to discover a different kind of music. A music that is not dependent on chord triads and their inversions, a music that uses gapped scales and modes. Lacking levers (in a bow to the historic) we find ourselves encouraged to try alternate tunings. We may play a different repertoire on our wire–strung harps than we do on our other harps.

All of these goals, all of this learning, all these experiences are possible on an historically informed wire–strung harp. Not one of these requires that your historic clàrsach be made to measure and decorated to the specifications of some surviving instrument. Your performance, your experience, is just as valid and you should never fear that you may be chided for playing a non–replica

harp, as if it is inferior, most certainly not by another harper. In fact, your creation of early music, and of the experience of historical performance, may be better than the person who has the perfect replica but does not take into consideration such things as context and purpose.

Most simply we play these harps for pleasure, whether ours alone, for family or friends, or a gathering of many people. But what about those expectations of that modern audience? Because it’s quite certain none of us will ever have the opportunity to play for an authentic medieval audience! What about all those differences in how people hear music today? We may raise the head on our harp a little to allow longer strings in the bass so we get the sound people expect. We may use silver or even gold strings to change the sound. Some may widen the sound box on their otherwise perfectly–measured replica harp because they want the sound that provides. Perhaps we play with a microphone so our hearing–impaired modern audience can hear us. If we play with other modern instruments, we might tune A=440Hz, add levers or blades, make concessions to modern times.

Many harpers also choose to play music from areas outside of the time and place where the wire–strung clàrsach began and flourished in the past.

We should be allowed to follow our muses without apology, and without disdain from our fellow harpers.

What would music be like today if resonating wire strings and diatonic music had not faded against the onrush of chromatic music? What would we be listening to? What would we be learning? Like other instruments that have survived from history, we would learn and play music from the instrument’s glorious past.

Detail of drawing from ‘The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland’ by MacGibbon and Ross (1887) p 253 (see Final Chords page on WireStrungharp.com for more information on the Kilcoy carvings and the source of this illustration.

We would also spend time simply enjoying the sound of our metal strings. We would remember the stories. We would play music of different times and places. We would feed our love of learning with this rare and beautiful music.

I have done these things. I continue to do them. I learn, experience the stories, value this home for the modal music I have always loved. And in this journey, one of my instruments has taught me more than any other; the smallest one of them all.

[1] Keith Sanger, Stone Images. 2003. The Wire Branch of the Clarsach Society. See also Final Chords on this website for further illustration and pertinent discussion on the Kilcoy Castle harp images.

[2] Robert Bruce Armstrong, The Irish and Highland Harps. Edinburgh, Scotland: David Douglas, 1904. plate facing page 154

[3] The Table of Images on this website provides a good visual reference of the different looks of the surviving harps.

[4] Edward Bunting, The Ancient Music of Ireland. Dublin, Ireland: Hodges & Smith, 1840. 31.

[5] My thanks to Bill Taylor for bringing this to my attention.

[6] Gianpaolo Gregori, La Chitarra Giustiniani

Antonio Stradivari 1681. Cremona: Fantigrafica Cremona, 1998. page XXIV (English translation, page XII presents the text in the original Italian). The full passsage in Italian appears below:

...le uniche chitarre sinora conosciute del periodo ‘classico’ della liuteria cremonese sono quelle di Stradivari e il Bellow sosteneva che la caratteristica che le distingue, in marcato contrasto con le chitarre decorate dei suoi contemporanei è

la classica misura ed eleganza eguagliata soltanto dai liutai modern.Ma non teneva conto, a mio avviso, degli strumenti raffigurati in molti dipinti dell'epoca (ad es.:

La buona venturadel valentin eLa chitarristadi Gerrit van Honthorst al Louvre) che fanno pensare che di chitarre per ‘veri musicisti’ ne venissero costruite moltissime, ma il fatt d’essere prive delle ridondanti decorazioni delle opera d’arte da ‘salotto’ (o da tavolo da toilette) le abbia portate più facilmente all distruzione.Così, sono pervenute in maggior numero quelle

preziose, e sono oggi più rare quelleordinarie. E quelle di Stradivari sono sopravvissute forse per puro caso, magari soltanto perchè esistevano ancora quando il prestigioso nome del loro autore aveva cominciato ad allettare i mercanti.

[7] Bernard D. Sherman, You Can’t Sing a Footnote: Susan Hellauer on Performing Medieval Music.

Inside Early Music. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. 43.

[8] David Johnson, Music and Society in Lowland Scotland in the Eighteenth Century. London: Oxford University Press, 1972. 32.

[9] Selected resources for this hearing

section of this lecture include:

Peter Kivy, Authenticities — Philosophical Reflections on Musical Performance

(1995) Peter, Kivy. Authenticities: Philosophical Reflections on Musical Performance. New York: Cornell University Press, 1995. Web.

Ardal Powell. Early Music Performance in the Age of Recording.

Early Music America Fall 2007: 34–38. Print.

Mark Katz. Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music.

Library Of Congress Webcasts. The Library Of Congress, 9 Nov. 2005. Web. 25 Feb. 2012. Capturing Sound.

(from an original live lecture given on 9 November 2005).

Thomas Forrest Kelly. Early Music Musings.

Early Music America Spring 2008: 7. Print.

Schubert’s great B–flat sonata was played twice: once...on a reproduction Confrad Graf fortepiano, and once...on a reproduction Steinway. Well, I guess it wasn’t a reproduction Steinway, but somehow it tilts the playing field to call one of the instruments a

reproduction.

John Rutledge. How Did the Viola Da Gamba Sound?

Early Music Jan. 1979: VII, 59–68. Print.

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.