The musicians John Bowie (1759–1815) and his younger brother Peter/Patrick (1763–1846) were natives of the parish of Tibbermore in Perthshire. The family home was at Huntingtower Mains, midway between the villages of Tibbermore and Huntingtower and about three miles west of Perth. Professionally Peter Bowie seems to have based himself in Perth as a music teacher and tuner, but John remained at Huntingtower, at least that was the address he used for his early publications of sheet music. [1]

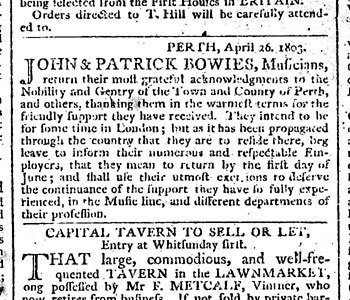

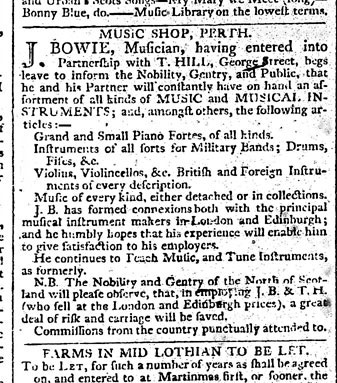

The brothers organised annual Dance Assemblies in Perth and following a joint visit to London in April 1803, presumably to contact wholesale suppliers of stock, John Bowie entered into a partnership with Thomas Hill to open a music shop in George Street, Perth, in July of that year; which continued until John’s death in 1815. Although John Bowie produced a number of his own compositions in sheet music form his main work was A Collection of Strathspey Reels & Country Dances; with a bass for the violincello or harpsichord, printed for him by Stewart at Edinburgh in 1789. The title is a little misleading as the work contains more than just dances and includes a section of Irish tunes preceding the section of interest here, the harp music starting at page 32 and running through to the end of the volume.

Bowie’s introductory account of how he acquired the harp tunes does not name his source or give the ‘Gentleman of Note’s’ family name but John Gunn in his work on the harp does. Quoting General Robertson of Lude, (probably the covering letter to the Highland Society which accompanied the two Lude harps to Edinburgh) [2], Gunn states that the source was ‘Colonel Colgear Robertson’ of the Strowan family. He further states that it was the colonel’s father who was a contemporary of John Robertson of Lude (d 1730), who had copied Lude’s harp tunes on the violin and passed them on to his son. [3]

Gunn would seem to have misread General Robertson’s handwriting and turned a ‘y’ into a ‘g’ as the source he identifies was Colonel Walter Phillip Colyear Robertson, (1743–1819), the younger brother of Colonel Alexander Robertson (1741–1822) who had adopted the title ‘of Struan’ on the restitution of the Struan Estate in 1784. Their father, who would have been a fairly young man when he had heard John Robertson playing the harp, was Duncan Robertson, 4th of Drumachuine. Although acknowledged as the heir to the Struan title on the death of his cousin, he was attainted following the failure of the rising in 1745/6, and he had fled to France with his family where he died still in exile at Givet in 1782 never having formally held the title or estate of ‘Struan’.

The two brothers, Alexander and Walter Phillip were brought up on the continent and gained their ranks through service with the Scots Brigade in the Dutch Army. [4] Too young to have been involved in the rising the act of attainder did not apply to them and so they were free to visit Scotland and on at least two occasions, in 1770 and 1772, the then Lieutenant W. Ph. Colyear Robertson used a Dutch passport to do so [5] However, the most likely period for John Bowie to have come into contact with him was after the Struan Estate was returned to the family in 1784 and possibly before the autumn of 1787 when the then Lieutenant Colonel Colyear Robertson returned to Holland on government business relating to the Scots Brigade. [6]

Bowie’s division of the ‘Ports’ into being composed for either Religious worship or for Heroic Subjects is curious as there is no reason to assign any of the ports he publishes to being used for worship, an unlikely musical event in most of post reformation Scotland in any case. Likewise the free use of the terms ‘Ancient’ to describe the tunes he published along with the blanket claim that they were all learned from the playing of the ‘famous Rory Daul’ have to be treated with a degree of circumspection. The statement that the said Rory Dall was a celebrated harper during the reign of Queen Ann along with the identification by Gunn of the source of the tunes being John Robertson of Lude, does avoid the usual confusion between the two ‘Rory Dalls’ but still leaves a problem.

The harper clearly identified here is the Scottish Roderick Morison, (An Clarsair Dall), but his biographer William Matheson has shown from contemporary records that the harper had died between late 1713 and before the death of Queen Ann herself on the 1st August 1714. [7] Therefore at least one tune, the air entitled The Battle of Sheriff Moor, which was fought on the 13 November 1715 and must date to then or later could not have been ‘learned from Rory Dall’. This does not exclude the tune from being in John Robertson of Lude’s repertoire and the evidence suggests it very definitely was.

Among the Lude papers there are several versions of Oran air Cath Sliabh an t–Siorraimh, (A song on the battle of Sheriffmuir), [8] one of which in appearance although undated, looks likely to have been contemporary with John Robertson. [9] This would suggest that the tune in Bowie was an instrumentalised version of a harp accompanied song air. This like all the other harp airs in the collection, was aurally transposed onto fiddle by Duncan Robertson and two generations later taken down from his son’s playing by John Bowie. Bass lines have been added, presumably composed by Bowie himself, which harmonise the melody.

This little collection therefore provides a window on some of the repertoire of an early eighteenth century Scottish harper although the view through that window is still obscured by the curtains of time and the method of its musical transmission via the fiddle.

Please follow this Catalogue link to return to the author index on the Library page.

[1] Edinburgh Courant 16 July 1801

[2] According to Gunn’s report pages 103–104 all the letters along with his report and the original drawings of the Lude Harps were placed among the records of the Highland Society. They are not there now but were probably a casualty of the large fire which destroyed a lot of the Edinburgh Old Town in November 1824. The Highland Society of Scotland’s current library copy of Gunn’s printed work was only purchased by them in 1937.

[3] Gunn John, An Historical Enquiry Respecting The Performance on the Harp, (1807). 96.

This book is accessible in the WireStrungharp.com library via this link: John Gunn’s Historical Enquiry

[4] National Archives of Scotland, (NAS), GD155/856

[5] NAS GD38/1/991 and 996

[6] National Register of Archives for Scotland, 358/23

[7] Matheson William, The Blind Harper (An Clarsair Dall), (1970), lxxii and footnotes

[8] The poem on the Battle whose first line is Dh’ innsinn sgeula dhuibh le reusan, listed as number 145 in Colm O Baoill and Donald MacAulay, Scottish Gaelic Vernacular Verse to 1730; A Checklist, (Revised Edition 2001).

[9] NAS GD38/1/1244/86–89. Early 18th century paper now in very poor condition containing seven verses written in an almost phonetic Gaelic spelling, each verse having a somewhat idiomatic matching translation.

Text submitted by Keith Sanger, 1 August 2012

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available by contacting us at editor@wirestrungharp.com.